John of Patmos foretold a cataclysmic end of the world as the point when each Christian should anticipate entrance into either heaven or hell. Many faithful people therefore sought connections to the higher realm through the saints, whom they imagined as residing in heaven. Legends written during the Middle Ages focused on the heavenly authority of saints, who had earned celestial positions for their good works, and of martyrs, who had died for their faith. Due to their influence in heaven, saints and martyrs offered to the faithful a hope of salvation, an expectation rooted in John’s descriptions of heaven. The prominence of the saints in medieval Christian culture thus grew directly from the promises of the Book of Revelation.

1A. ROMAN TYRANNY IN THE AGE OF PROPHECY

John of Patmos wrote when Christians and Jews suffered persecution under pagan Roman emperors. In 70 C.E. Roman armies destroyed the Temple of Solomon, a woeful tragedy for both Jews and Christians. Imagining punishments for this misdeed, John used the symbolic language of earlier prophets as well as old tales of resisting tyranny to show that his Roman enemies deserved divine wrath.

John’s animosity toward Rome, however, became increasingly problematic in the fourth century, after Christianity achieved legitimacy in the empire. Despite its controversial contents, the Book of Revelation gained acceptance by most Christian communities for its fascinating imagery promoting salvation.

In this scene accompanying the opening sentences of the Book of Revelation, an angel descends from heaven to present a text to John of Patmos. John stands before a throne to take in the celestial vision. The heavenly stars foreshadow an offer of salvation at the end of time.

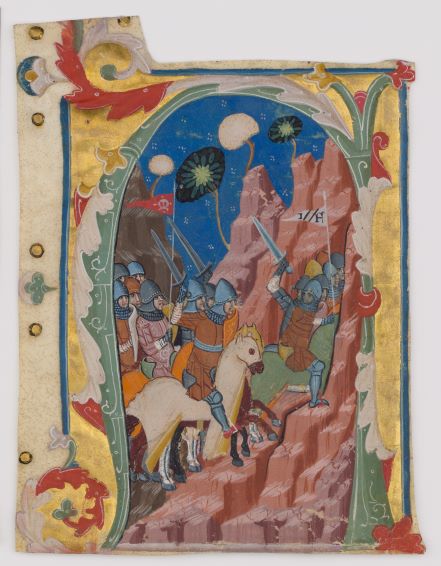

Illuminated manuscripts feature texts supplemented by images, highly decorated letters, and additional ornament at the margins.

The Book of Revelation draws heavily from Jewish and Christian tales of communities defying persecution, like the Maccabean revolt in the second century B.C.E.

The Maccabees were members of an ancient Jewish family who resisted religious oppression from their Greek rulers. In the later medieval Christian imagination they were viewed as precursors to armed crusaders, whom they resemble in this decorated letter.

As John writes the Book of Revelation on his island home of Patmos, he sits next to a crowned, seven-headed beast. The crowns symbolize blasphemy and refer to earthly, rather than divine, authority. In contrast to the beast, a heavenly entourage led by God in the upper right offers a hope of redemption.

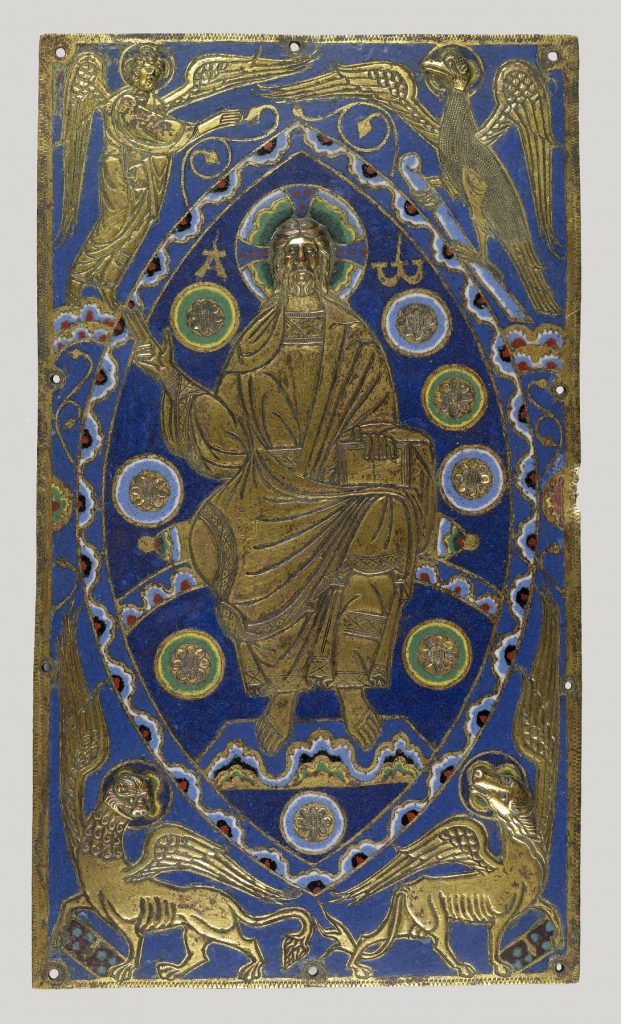

This cross was originally mounted on a long staff. On the front, the crucified Jesus was worked in copper so that his form could appear prominently when raised aloft during a procession. On the reverse, Jesus is shown surrounded by the winged heavenly creatures (angel, eagle, lion, and ox) described in the Book of Revelation to remind viewers of the connections between the Crucifixion and the return of Jesus at the end of time.

1B. JUDGEMENT AND SALVATION

The Book of Revelation says Jesus will judge humanity at the end of time. Most medieval images depicting this event, known as the Last Judgment, feature Jesus enthroned and accompanied by his mother Mary. Artists identified Mary as the pregnant woman clothed in the sun whom John of Patmos describes in the Apocalypse.

Mary, known for her goodness and purity, was commonly depicted in artworks requesting her son to act with compassion. The hope for mercy was thus juxtaposed with the fear of judgment—a tenuous balance in which Mary’s sympathy potentially lessened the threat of Jesus’ condemnation.

This enamel plaque was likely originally affixed to the outer bindings of a medieval manuscript. When the manuscript was presented before the public, the colorful enamels dazzled viewers.

The four winged creatures surrounding Jesus symbolize the four authors of the Gospels who wrote about Jesus’ life: an angel for Matthew; an eagle for John the Evangelist; an ox for Luke; and a lion for Mark.

Here, Mary and John the Evangelist beg for Jesus’ compassion on behalf of resurrected souls emerging from their graves. Angels sounding their horns announce that the final judgment is a prelude to resurrection. Jesus’ multiple wounds emphasize the suffering he endured on the cross, while Mary bares one of her breasts to remind Jesus of a mother’s mercy.

Mary, crowned and enthroned as the queen of heaven, holds the child Jesus on her lap. Mary was considered the “Throne of Wisdom,” since her lap shelters her son, depicted as a miniature adult to emphasize his advanced intelligence.

The fruit in Mary’s hand marks a contrast to Eve, who disobeyed God by taking up the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden. Unlike Eve, Mary’s obedience made her an example for viewers seeking salvation.

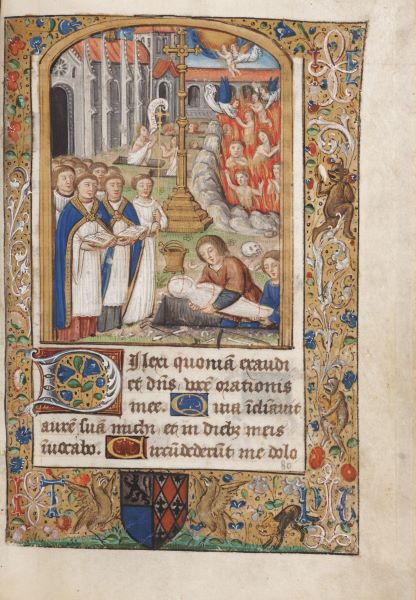

This burial scene features monks leading prayers within a medieval monastery and accompanies texts that commemorate the souls of the dead. In the upper right, flames engulf bodies in Purgatory, a place between heaven and hell where deceased souls await potential forgiveness for earthly sins.

Celestial angels lift up the lucky souls who have received redemption, illustrating that the deceased on the path toward heavenly salvation continued to receive beneficial prayers from the living.

1C. RESURRECTION

The Book of Revelation indicates Jesus will return at the end of time, when the dead and buried will be resurrected. According to John of Patmos, this resurrection will be physical as well as spiritual. Souls will be reunited with their bodies and claw their ways out of the earth to learn their fates on Judgment Day. Then, the reanimated bodies of those chosen for heaven will join the saints residing there.

During the Middle Ages, a common practice was to visit the earthly graves of martyrs and saints whose physical remains were thought to provide access to spiritual power.

Two men with swords decapitate two unidentified martyrs in this circular, ornate panel originating from a larger stained glass window.

Images of the persecuted martyrs—people who died for their faith—allowed medieval viewers to contemplate their holy virtues as well as the celestial realm, where the saints and martyrs were presumed to reside. As sunlight filtered through the colored glass, the image linked violent sacrifice in this world with a glittering, heavenly afterlife.

This fragment of a stained-glass window shows a body reunited with its soul at the moment of resurrection, as described in the Book of Revelation. Clad in a burial shroud, the man pulls himself from a grave symbolized by the plank of a casket.

The lobed glass panel was originally integrated into a larger rose window, a circular installation of jewel-like stained glass designed to fill a church interior with colored light.

In 1513, the Belgian goldsmith Nicolas Croisart reused a 200-year-old enamel medallion to provide the outer decoration for a pyx, a small container protecting the communion wafer used in Christian mass.

Jesus rests upon a rainbow, a reference to God’s Biblical promise never to flood the earth again after Noah’s deluge. The sword and the lily, symbolizing justice and mercy, emerge from Jesus’ mouth. Mary and John the Baptist kneel beside him, interceding for humanity.

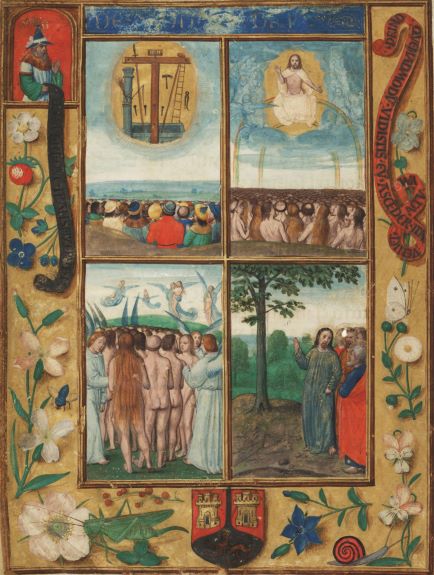

The upper left scene of this page depicts crowds on the ground gazing up at torture implements used during Jesus’ crucifixion. To the right, the unclothed figures witness Jesus in judgment after having accepted his teachings. Some are welcomed into heaven by angels in the lower left scene. On the lower right, Jesus assures the apostles that predicting the end times is as straightforward as forecasting summer’s arrival when a fig tree sprouts anew.

The text on the scroll held by Zacharias in the upper left: “VIDEBU[N]T IN QUE[M] TRASFIXERU[N]T” (“They will look upon the one whom they pierced”). The text in the margin in the upper right: “PRIMO QUEMADMODU[M] VIDISTIS EU[M] ASCE[N]DER[E] ITA VENIET ACTU. . . UM” (“Just as first you saw him ascend [into heaven], so he will come [into heaven]”).

This decorated letter ‘R’ once belonged to a medieval hymnal. It is ornamented with a scene of angels elevating the dead from open graves prior to judgment.

Jesus, displaying the wounds from his Crucifixion, sits upon a green rainbow, symbolizing the hopeful promise of new life after the great flood recounted in the Biblical story of Noah. Flanking Jesus, his mother Mary and John the Baptist plead for mercy on behalf of the raised souls.