The culmination of the Book of Revelation is an epoch of peace. All earthly battles will cease and the war-torn city will be superseded by a celestial “New Jerusalem,” which Christian commentators called “the city of peace.”

Artists and theologians thus imagined two Jerusalems. While the physical Jerusalem is located in the Middle East, the heavenly Jerusalem is aspirational and eternal. The earthly Jerusalem became a center for Christian pilgrims to experience the events of Jesus’ life. Fascinated by visions of the heavenly Jerusalem, artists used the imaginary city’s golden streets and bejeweled walls as allegories for celestial bliss. John of Patmos offered promises of the celestial Jerusalem to counteract anxieties over destruction. Yet his text also sparked an intense interest in the existing city of Jerusalem that continues to this day.

3A. SHARED SACRED SPACE

The physical city of Jerusalem is identified in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam as the place where heaven and earth meet. In the Jewish tradition, Jerusalem was the site of Solomon’s Temple, where priests communed with the divinity. For Christians, the city was the site of Jesus’ death and resurrection. In Islam, the prophet Muhammad dreamt of traveling to heaven by ascending from the “farthest mosque” located in Jerusalem. Although considered a city of peace, Jerusalem became one of the world’s most fiercely contested spaces and remains so today.

A man unearths three crosses in Jerusalem at the direction of Helena, mother of the Roman emperor Constantine. Through a miraculous sign, Helena verified one as the so-called True Cross on which Jesus was crucified. After campaigns to recover the physical remains from Jesus’ lifetime, Constantine rebuilt Jerusalem as a Christian city in 325 where future pilgrims were welcomed.

This carving and the relief below of Helena originally belonged to a longer narrative sequence decorating an altar.

This relief shows Helena, mother of the Roman emperor Constantine, authenticating the True Cross. She identifies the relic of Jesus’ crucifixion by using the cross to raise a man miraculously from the dead. Church authorities further validate the cross, since a bishop wearing a mitre, the pointed cap of a church official, baptizes a kneeling figure in the foreground.

The depiction of the figures in fifteenth-century clothing makes the old legend appear timeless.

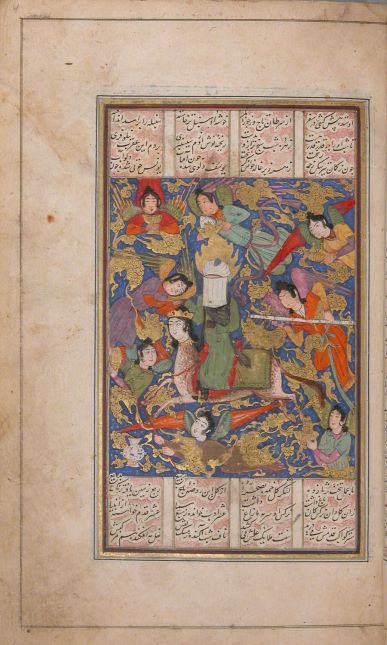

Here the Islamic prophet Muhammad rides the winged horse Buraq on an imagined “night journey” to heaven. The scene accompanies a poetic text by the Persian author Nizami. In the Islamic holy text of the Qur’an, Jerusalem was the point of departure for Muhammad’s dream-like experiences of heaven.

The veil covering Muhammad avoids the blasphemy of showing his face, since figural images were prohibited in Islamic religious spaces and occurred only rarely in secular contexts.

3B. The Millennium

When will peace begin? According to the Book of Revelation, Satan—released from his chains—will launch a final war against God’s people in which he will suffer his ultimate demise. Earth will then experience one thousand years of peace.

John further predicts that twenty-four elders accompanied by saintly judges will preside in Jesus’ place over this peaceful kingdom for a millennium. These elders were first described in the Book of Revelation as the guardians of God’s throne. Artists were enthralled with images of the twenty-four elders, since they helped believers envision a heavenly realm.

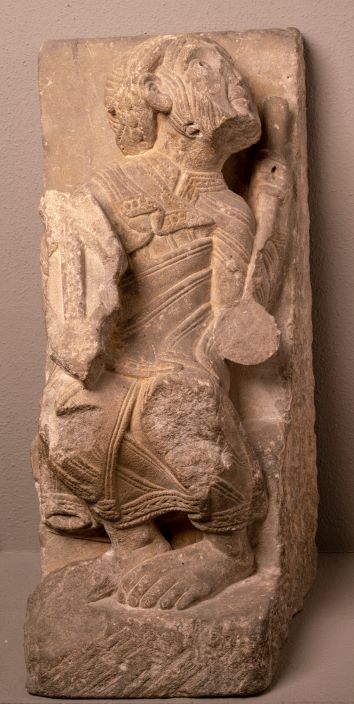

This figure represents one of the twenty-four elders described in the Book of Revelation as belonging to the group who might rule in Jesus’ name during the final epoch. He wears a nimbus, or halo, instead of a traditional crown. In his right hand he holds a musical instrument and in his left a perfume flask, representing the music and sweet scents of the heavenly court.

One of the twenty-four elders from the Book of Revelation holds a vial in his left hand and props a stringed instrument on his knee, producing the delightful music of heaven. With his slightly twisted posture and his head lifted up, he communicated with the other elders whom he originally accompanied in the portal sculptures of a French or Spanish church.

This weathered carving depicting one of the twenty-four elders of the Apocalypse retains much of the figure’s original dignity. The limestone sculpture originates from the exterior of a church in Parthenay, France where it clearly was exposed to the elements.

Based upon a comparison with other sculptures of the apocalyptic elders who carry vials and musical instruments as attributes, this crowned figure probably once held a vessel in his right hand.

3C. Paradise Regained

“I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband” (Revelation 21:2).

John’s final vision in Revelation was of an eternal peace that surpassed all understanding. To capture such ideas, prophets like John relied on fantastic allegories infusing heaven with earthly features. For example, he provided human attributes to the celestial city’s decorated walls, likening them to a bride’s ornamented garments.

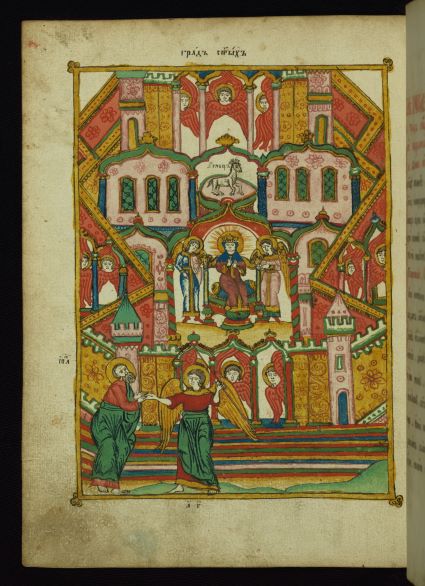

The Book of Revelation’s hopeful messages inspired depictions of the well-appointed walls of the heavenly Jerusalem, where the lamb presides as the symbol of peace.

Celestial Jerusalem with its jewel-studded walls has descended from heaven to replace the tarnished, earthly city. In the center, a bride awaits her marriage to the Lamb of God, a metaphoric figure who rules over heaven in the Book of Revelation.

This manuscript was created by the “Old Believers,” a Christian sect of dissenters in Russia. Denied access to the printing press, the group copied books by hand as a throwback to medieval traditions of manuscript production.

This dish features the apocalyptic lamb, a symbol for heavenly rule and peace. The cross in the lamb’s halo indicates that he represents Jesus, who, in John of Patmos’s vision, ruled in heaven as a lamb. Jesus’ authority is indicated here by the staff of rulership. In the Book of Revelation, the lamb is slain after submitting to the will of God but is subsequently entrusted with the judgment of humankind.