Horrific creatures symbolizing malevolent powers inspired widespread fascination with the Book of Revelation during pre-modern times. Allegorical beasts and demons faced punishments in John’s narrative, since the Apocalypse pitted satanic creatures in lasting but ultimately unsuccessful battles against those destined for heaven. John’s text assured believers that these clashes between good and evil forces were dramatic precursors to the era of peace.

However, the Book of Revelation did not denote a decrease in either war or religious conflicts. Indeed, apocalyptic texts can be indirectly associated with medieval holy wars, since some people interpreted John’s text as supporting military vengeance against nonbelievers for their supposed assaults on God’s followers. This contested legacy of interpretation continues into our modern era.

2A. BEASTS, THE HORSEMEN, AND THE HARLOT

The Apocalypse did not lack villains. Its cast of characters gave artists a limitless visual toolkit with which to delight and frighten audiences. The torments included the hell mouth devouring condemned souls, four horsemen bringing forth wars and plagues, and a seven-headed dragon.

Among the notorious villains of Revelation was the whore of Babylon, who was drunk on Christian blood. The Apocalypse describes the legendary harlot as having arrived from Babylon, a city that launched a devastating sack of Jerusalem long before the Roman assault on that city, making her a symbol of the evil John saw in Rome.

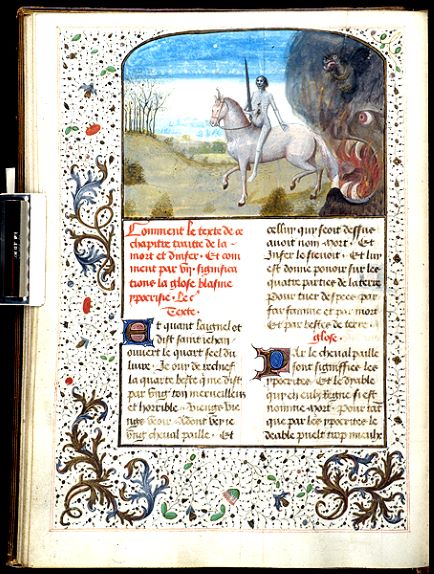

In this illustrated manuscript, a skeletal rider mounted on a ghostly horse emerges from the mouth of hell and enters into a desolate landscape. The hell mouth belongs to a sulfurous, sooty dragon who guards the underworld. As an incarnation of death, the horseman’s cadaverous body resembles the victims of late medieval Europe’s plague pandemic, which decimated the population.

This richly illustrated apocalypse manuscript was made for Margaret of York, the Duchess of Burgundy.

Here, the German artist Albrecht Dürer depicts the clamoring threat of four horsemen who foreshadow impending catastrophes. The horsemen—metaphors for death, famine, war, and plague—wreak apocalyptic havoc by trampling sinners underfoot. In the lower left, a beast consumes a bishop wearing a mitre, the pointed headdress of a church official, indicating that even high-ranking clergy may not be saved.

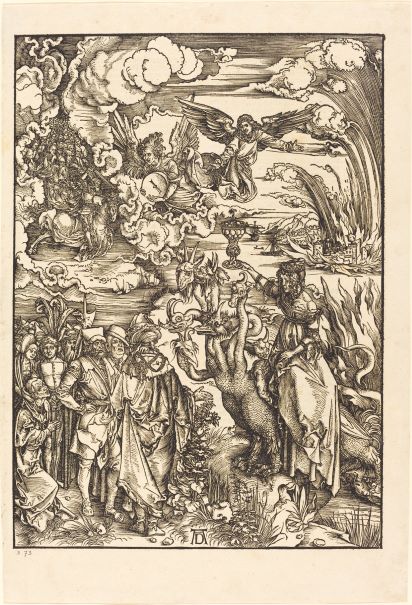

Dürer’s woodcut features the whore of Babylon, seducing crowds with her finery and wealth. She rides upon an evil creature: the seven-headed beast with ten horns. In the background, flames consume the city of Babylon, while heavenly armies prepare for battle.

Dürer sympathized with critics of the pope’s wealth and the Vatican’s luxury. For some viewers, the harlot’s lavish garments may have symbolized the excessive corruption of papal Rome.

2B. WAR IN HEAVEN

The Book of Revelation describes wars between saintly armies and their demonic foes led by various beasts. As foretold by the prophets, these clashes precede the final act of judgment in the Apocalypse and the end of the world.

Saints and angels claim victory in these battles. In the most iconic battle scene, the Archangel Michael descends from heaven and slays the dragon that symbolizes Satan, announcing the destruction of an evil empire. Medieval artists were captivated by these dramatic struggles.

The enameled metalwork of this crozier, or bishop’s staff, shows the Archangel Michael conquering the dragon at the climax of the War in Heaven, a dramatic episode in the Apocalypse.

To emphasize continuing struggles against evil, the figure of Michael is encased by a snake-like form ending in a stylized animal head that threatens the Archangel. The curved shepherd’s crook indicates that the bishop holding this crozier had acquired a pastoral role over his flock.

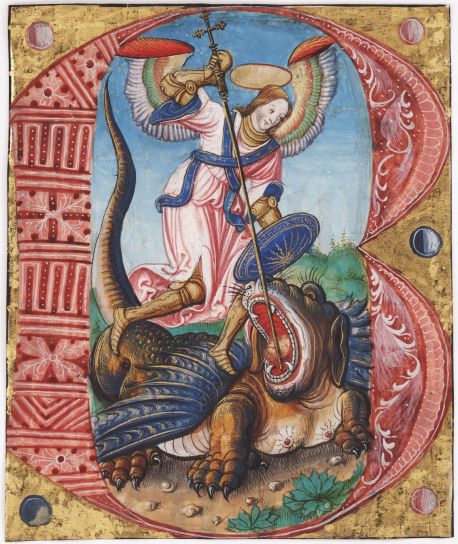

This initial ‘B’ originates from a liturgical manuscript containing an outline of the rituals for the mass. It once accompanied a text describing the feast dedicated to Archangel Michael.

Michael is shown wearing gilded armor underneath a liturgical robe, indicating his sacred status as he defeats an evil dragon during the war between Heaven and Hell at the end of the world. Christian crosses decorate his blue sash and form the handle of his spear.